|

| ||||||||

|

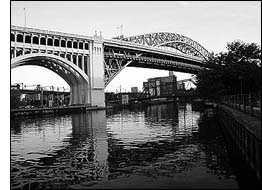

An Historical Perspective CYDNEY MILLSTEIN Abstract For years Kansas City, Missouri, sought solutions to connect the commercial and business district on the edge of the bluffs with the industrial district 200 feet below where wholesale houses, rail yards, and stockyards are located in the bottom lands of the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas rivers. In the last decades of the 1800s, inaugural and subsequent cable lines provided access into the central industrial district, but these harrowing thoroughfares were not engineered to carry vehicular traffic of the new century. Replacing the dilapidated cable-car trestle on Twelfth Street, the new double-deck, 2,300-foot long reinforced concrete viaduct provided the necessary direct link when it was completed in 1915. Designed by the renowned Kansas City firm of J. A. L. Waddell and John Lyle Harrington, and built by the Graff Construction Co, Seattle, the unusual structure displays a prominent bowstring arch span and 45 girder spans masked as arches at the upper deck. As originally constructed, the upper deck provided a 30-foot roadway for vehicular traffic, a double-track electric railway on an independent right-of-way, and a single 5-foot sidewalk, while the lower deck provided a clear roadway for heavier commercial traffic. Quite possibly inspired by the surrounding monumental streetscape and the aesthetic philosophy of the erudite architect Henry Van Brunt, Waddell and Harrington incorporated into their design Classically inspired architectural elements that are both structurally efficient and ornamental. Today, the Twelfth Street Trafficway Viaduct, although modified in the 1960s, stands as a legacy to Kansas City, the engineers, and the contractors who conceived and built this exceptional span. •

Stretching from the bluffs at the edge of Kansas City Missouri's business district to the valley of the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas rivers is The Twelfth Street Trafficway Viaduct, a double-deck, reinforced-concrete bridge designed by the renowned Kansas City firm of Waddell and Harrington and completed in 1915. The structure, which today stands as an uncelebrated and worn monument was, at its inception, hailed as a milestone in Kansas City's continued effort to transport people and merchandise via the central axis of the city and by the engineering profession nationwide. There are few cities in the U. S. where the railroad and wholesale district is so clearly separated from the central business district as in Kansas City (see figure 2). The industrial area is also separated from the business center of Kansas City by the bluffs that extend to the north and south. Traffic between these locations has always been heavy and, until the completion of the Twelfth Street Viaduct, was seriously handicapped by steep grades and indirect routes. All vehicular traffic had no thoroughfare to and from the heart of the business center from 6th Street on the north to 23rd Street on the south, a distance of more than 1 1/2 miles.1 Although the Ninth Street Incline, the 8th Street Tunnel and "EL," and twin toll elevators conveyed products and people to and from the busy industrial section, the promise to build a suitable passageway linking 12th Street, the principal thoroughfare of Kansas City, was made a focus of more than one political campaign. The first direct line was the initial 12th Street Viaduct, an 1887 iron structure designed by the Kansas City Bridge and Iron Company for cable railway and pedestrian traffic, but it was the present Twelfth Street Viaduct that assured a direct and safe route. In November 1909, the city council of Kansas City, Missouri, passed an ordinance that extended the franchise of the railways to operate along Twelfth Street, provided they build the replacement structure.

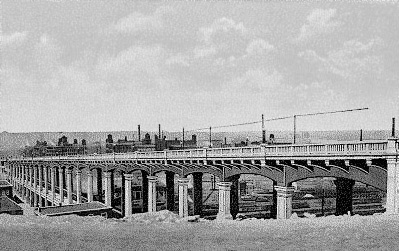

Waddell and Harrington's plans for the new viaduct, adopted by the city in April 1912, called for a 2,265 foot structure with a maximum height of 110 feet at the bluff, and 45 upper deck girder spans of 33 to 56 feet. As originally planned, the top deck, at a grade of 5.5 %, provided a 30-foot roadway for vehicular traffic, a double-track electric railway on a 21 1/2-foot independent right-of-way, and a single 5-foot sidewalk. The lower deck, consisting of 27 through-girder spans, provided a clear roadway 30-feet wide on a variable grade of 3% for slower team traffic carrying heavy loads. Reinforced concrete stairways afforded access to the upper deck of the viaduct at three cross-streets. The highways of both decks were paved with creosoted wood blocks, separated transversely to assure good foothold for horses.2 According to Willis Grinstead, former vice-president of Harrington and Cortelyou (Kansas City, Missouri), a successor firm to Waddell and Harrington, the Twelfth Street Trafficway Viaduct is one of the earliest examples, if not the first example, of a concrete double-tiered bridge in the United States.3 Furthermore, its design features some uniquely engineered elements, including the 134-foot bowstring arch and reinforced concrete columns. Several distinctive architectural elements were also implemented. To solve the problem of spanning multiple railroad tracks where piers had to be avoided, Waddell employed the use of encased bottom chords of eye-bars at the lower deck elevation, taking up the arch thrusts. Because the available clearance was modest, the floor beams of the lower deck were constructed of steel I-beams encased in concrete and riveted to encased steel hangers. The battered columns, no two alike, are more massive on the north side of the viaduct due to the necessity of carrying the heavier load of the electric railway. The bottom sections of the columns have, on each narrower face, a battered pilaster to carry the longitudinal girders of the lower deck. The principal elements of labor cost of the structure were based on the construction, erection, and removal of the forms and falsework all built to dimension in carpenter shops on site. The concrete mixing plant, the distribution hopper for concrete, and the cable operated construction railway used to deliver concrete as work on the bridge proceeded, all contributed to a systematic handling of labor and materials. This logical order contributed to rather swift construction, as the viaduct was completed in just fifteen months. An average of 200 men, of whom nearly 150 were carpenters, worked nine-hour days to erect the structure.4 In considering the use of varying architectural treatment for the viaduct, further setting it apart from other concrete structures of the time, Waddell was most certainly influenced by the philosophy of architect Henry Van Brunt who, at the age of 50, moved to Kansas City in 1887, the same year as Waddell.5 Like Waddell, the nationally prominent Van Brunt was a prolific writer and critic, with essays in such periodicals as the Atlantic Monthly. At his request, Waddell included Van Brunt's philosophy of aesthetics in bridge design in several of his own publications, including De Pontibus of 1898, and reprinted sixteen years later in Bridge Engineering.

"It is in vain," Van Brunt railed, "that the conscientious engineer occasionally attempts to compromise with grace by ornamenting his intersections by rosettes or buttons . . . or by rearing a sort of arch or portal of triumph at the entrance to his bridge with a lavish display . . . But the compromise comes too late, the main essential lines cannot be condoned by afterthoughts of this sort . . ." "The eye," continued Van Brunt, "requires to be satisfied as well as the trained intelligence, and demands not only grace of proportion, but a certain decorative emphasis expressive of [s]pecial functions."6 As an example, Van Brunt cited the Doric order of the Parthenon, which "should still be lovely without the sculptures of its friezes, metopes and pediments. Its columns, reduced to dimensions . . . were so treated with entasis, capital and fluting as to express exactly, members in vertical compression."7 And so the columns of the Twelfth Street Viaduct were designed, in part as a response to Van Brunt's keen sense of beauty, and in part, perhaps, to the Classically-inspired detailing and rhythm of the surrounding 19th- century streetscape. The treatment regards the verticals not merely as posts, but as tripartite columns with base, shaft and capital. Additional aesthetic considerations include: curved girders at the underside of the upper deck; bold, curved, cantilevered brackets, and paneling at the lower deck girders. To give uniformity to the whole and preserve the unity of effect, despite the great variation in column height, span lengths were made smaller near the lower end of the structure.8 On March 18, 1915, the Twelfth Street Trafficway Viaduct officially opened for streetcar and vehicular traffic. Total cost of construction was reported at $625,000.9 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

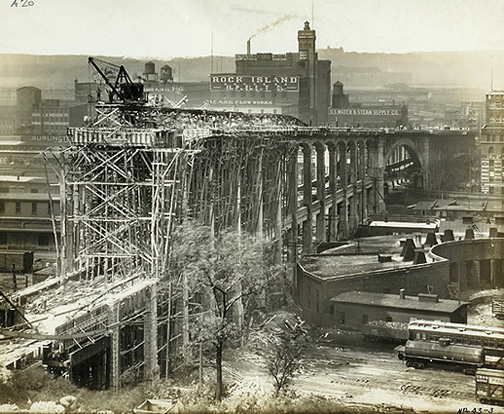

| Twelfth Street Trafficway Viaduct under construction. | |||||||||

|

Additional Comments Regarding the Physical Description Because of the significance of the Twelfth Street Viaduct in the field of engineering, it is important to further mention some of the interesting features of this monumental span. Information regarding design elements, beyond the above description of its general design, were excerpted from several contemporary engineering articles, including Engineering News, Engineering Record and Engineering and Contracting. The bowstring arch of the viaduct has a rise of 24 feet and is composed of two arch ribs spaced 40 ft. on centers which carry the upper (cantilevered) and lower decks. The lower deck is suspended by hangers, and the upper deck is supported on columns except at the center, where spandrel walls rest directly on the arched ribs. To provide a rigid structure that would not deflect much under loads, the arch was designed as a fixed arch. As the springing points are above the lower deck floor, it was considered advisable to fix the arch by providing steel shoes at each springing, and tying the shoes together with eyebars to take the horizontal thrust. Steel girders embedded in concrete were used instead of the usual reinforced-concrete longitudinal girders in span Nos. 1 and 2 of the upper deck at Hickory Street and in the lower deck for span No. 15 at Mulberry Street. Between the girders are cross-girders composed of a web plate, four flange angles and cover plates and between these are stringers of the same section, but shallow enough to fit between the flange angles. Horizontal gusset plates are fitted at the intersections of this framing and have holes to which the wire cloth reinforcement of the slab is wired. The longitudinal girders of the upper deck are made continuous over three spans, with cast-steel shoes for the expansion bearing at the ends and resting directly on the two intermediate columns. Between these are cross-girders in line with which are the cantilever brackets supporting the overhanging portions of the slab deck. The longitudinal girders of the lower span are in one-span lengths, as they fit between the columns and rest upon the pilasters. The significance of the Twelfth Street Viaduct lies not only in its importance as a major link between the industrial and central business districts of Kansas City, but certainly for its place in the field of engineering. As stated in the 1994 Missouri Historic Bridge Inventory, the viaduct is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (under criterion A and C). It's importance is discussed as follows:

Additionally:

Deterioration, Modifications and Controversy In September 1963, Mayor Ilus Davis discussed the closing of the historic viaduct due to its general disrepair. Since the Kansas City Transit abandoned operations of the span's top deck, and turned full control back to the city, weeds were growing where the bus line once operated and sections of pavements were "held in place by boards and ropes."12 As a result of an engineering study by the Howard Needles Tammen and Bergendoff (HNTB, Kansas City, Missouri), completed on June 19, 1964, it was determined that the bridge suffered from "continuing, progressive deterioration [which] may result in the failure of various parts of the structure under the vehicular loads presently being carried."13 Cracked concrete and deterioration of expansion piers and longitudinal girders was also noted in the report. HNTB's study of the bridge recommended widening the upper deck to four lanes to carry vehicular traffic and eliminating the lane originally utilized by streetcar rails. The total cost to rehabilitate the viaduct was $1,800,000, as reported by HNTB. Plans for the repair and conversion of the bridge subsequently were prepared by HNTB and Massman Construction Company, Kansas City, the low bidder at $1,976,104, was awarded the contract.14 Rebuilding of the Twelfth Street Viaduct resulted in the rerouting of approximately 27,000 cars daily. The upper and lower decks, as well as the base level of the viaduct over the railroad tracks, were shut down on February 28, 1965. Construction began on March 1. After 8 1/2 months of work, the upper deck of the Twelfth Street Trafficway Viaduct was ready for traffic, in time for opening day of the American Royal in October 1965. The middle and ground levels were finished in August 1966. Three years later, Massman Construction Company filed a lawsuit against the City of Kansas City for $1,211,445 for additional costs, contending that the deterioration of the bridge was worse than the city indicated.15 The City claimed that Massman caused damage to the span during construction and that the company's bidding procedure was inept. An inspector stated that the removal of column caps with jackhammers put the project behind schedule and as a result blasting was used. This method damaged girder ends, columns and cross girders. Additionally, cantilever brackets were cracked and had to be replaced.16 The suit was brought to a close in August 1970 when Massman Construction Company was awarded $700,000.17 In addition to the widening and conversion of the upper deck to vehicular traffic, alterations of the Twelfth Street Viaduct include replacement of the original balustrade with modern metal pipe guardrails and upper solid concrete balustrade with recessed panels, removal of the steel trolley poles, cast-iron lamp posts (upper deck) and cast-iron lamp brackets (lower deck), stairways and landings. John Alexander Low Waddell The career of John Alexander Low Waddell is so extensive, it would be impossible, in the space allotted here, to list his extraordinary accomplishments that led him to be recognized by his colleagues as "a genius in the art of bridge building and one of the outstanding international engineers in his field."18 For his work, which included the design of iron, steel and concrete bridges in twenty-five cities in the U.S. and Canada, numerous railway bridges throughout North America, and spans in Mexico, Cuba, Japan, China, Russia and New Zealand, the ASCE in 1931 awarded him the first Clausen Gold Medal honoring his contribution to the social and economic welfare of the Engineering profession.19 J. A. L. Waddell, a native of Canada, began his education at Trinity College School in his home town of Port Hope, Ontario, and subsequently, because of John's ill-health, his parents sent the 16-year old Waddell to China on the tea clipper N. B. Palmer for a 10 month voyage. On his return, he briefly attended a business college in Toronto in 1871. That same year, he entered Rensselear Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York, one of the oldest engineering schools in North America, where he received a Civil Engineering degree in 1875. Waddell began his career as a draftsman for the Marine Department at Ottawa, Canada, and in 1876-77, served as engineer with the Canadian Pacific Railroad. In 1878, Waddell returned to RPI and spent two years on its faculty and in 1881, at the age of 26, moved to Council Bluffs, Iowa, to work as Chief Engineer for Raymond and Campbell Bridge Builders. One year later, he received a Masters in Engineering from McGill University, Montreal, Canada and married Ada Everett, from Council Bluffs.

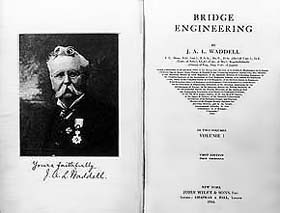

Accompanied by his sister, Josephine, Waddell and his bride sailed for Tokyo that same year, for Waddell had accepted a position as chair of civil engineering at the Imperial University. During his four-year tenure, Waddell published several technical articles, many of which were incorporated into his first book The Designing of Ordinary Highway Bridges, published by John Wiley and Sons, New York. It was widely accepted as a standard textbook for six years until Waddell declared it out-of-print because wrought iron had been displaced by structural steel, dramatically changing bridge building.20 His ensuing output of publications, including the standard two volume Bridge Engineering of 1916, is staggering.21 On his return to the U.S. in 1886, Waddell was hired as western representative for Philadelphia's Phoenix Bridge Co. and the Phoenix Iron Company in Kansas City, Missouri.22 Six years later, the successful and tenacious thirty-eight year old resigned his position with Phoenix to start his private practice as a bridge designer and consultant. For the next half century, Waddell was referred to as "one of the best known bridge engineers in the United States."23 From 1887-1899, Waddell worked with several assistants including Ira G. Hedrick, with whom he formed a partnership on January 1, 1899. The firm Waddell and Hedrick lasted until 1906 when John Lyle Harrington (see figure 23) entered the business as Waddell's partner. The affiliation of the highly successful team of Waddell and Harrington ended in 1915 apparently on account of Harrington's inflexibility and Waddell's vanity.24 In 1917, J. A. L. Waddell carried on the practice of a brilliant engineering career with his son Everett as Waddell & Son, Inc., until 1920, the year Everett unexpectedly died. After practicing over thirty-three years in Kansas City, Missouri, Waddell moved his office to New York City and in 1927, he took on as partner his principal assistant engineer Shortridge Hardesty under the name of Waddell & Hardesty. Shortly following a stroke, John Alexander Low Waddell died on March 3, 1938.25 Of the extensive catalogued works by Waddell, it is appropriate to mention a few of the more outstanding bridge designs extant in the United States. These include:

| |||||||||

|

Notes: 1. L.R. Ash, "Discussion: Trafficway Viaduct, Kansas City, Missouri," ASCE Transactions 80 (1916): 563. Waddell employed Lewis Russell Ash in 1901. When the firm Waddell & Harrington dissolved in 1914, Ash joined Harrington and Howard to form a partnership that lasted until 1928. The successor firm, Howard Needles Tammen and Bergendoff, is located in Kansas City, Missouri. Ash had a principal part in solving the solution of creating trafficways into the West Bottoms and Kaw Valley District, which resulted in the construction of the Twelfth Street Trafficway Viaduct and later, the Twenty-Third Street Viaduct. 2. E.E. Howard, "The Twelfth Street Trafficway Viaduct, Kansas City, Missouri," ASCE Transactions 80 (1916): 484-532, gives a thorough description of the viaduct. See also "The 12th Street Double-Deck Viaduct at Kansas City," Engineering News 73 (January 7, 1915): 10-15; "Construction of the Twelfth St. Trafficway Viaduct, Kansas City, Missouri," Engineering and Contracting 44 (October 27, 1915): 326-332; and H.H. Fox, "Half-Mile Concrete Viaduct Provides Double-Deck Trafficway in Kansas City," Engineering Record 71 (January 6, 1915): 164-166. 3. Willis Grinstead, interview with the author, March 26, 1997, Kansas City, Missouri. R.N. Bergendoff, in his article "Notable Bridges in the United States," Civil Engineering 7 (May 1937): 323, stated that "as a concrete structure, the Twelfth Street Viaduct . . . is outstanding in design and unusual in type." 4. E.E. Howard, "The Twelfth Street Trafficway Viaduct, Kansas City, Missouri," ASCE Transactions 80 (1916): 525. 5. Henry Van Brunt, formerly in practice with William Ware in Boston, teamed with Frank Maynard Howe in Kansas City, Missouri. In 1898, Van Brunt was elected president of the AIA. 6. Henry Van Brunt, Letter to J. A. L.Waddell. Reproduced in J. A. L. Waddell, De Pontibus: A Pocket-Book For Bridge Engineers (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1898): 41-42. 7.Ibid., 43. 8. "Construction of the Twelfth St. Trafficway Viaduct, Kansas City, Missouri," Engineering and Contracting: 329 (see fn. 2). 9. The total cost of the entire project, including land was $1,000,000. Funding for the project was secured through a combination of a general bond issue ($475,000), by assessments ($325,000) and by a contribution from the Metropolitan Street Railway Company ($200,000). 10. See section "Discussion," included in Howard, "The Twelfth Street Viaduct," 533. 11. Clayton B. Fraser, "Twelfth Street Trafficway [Viaduct]," Missouri Historic Bridge Inventory Form, September 24, 1994. The inventory incorrectly states the date of the bridge's construction as 1913-1914. 12. "Bridge in Poor Repair," Kansas City Times, 9 September 1963. 13. "City is Advised to Rebuild Span," The Kansas City Times, 4 June 1964. 14. Consulting engineers were against building a new viaduct as construction costs were estimated at over $3 million. 15. "Probe Facts In a Suit Against City," The Kansas City Star, 23 July 1969. 16. "Viaduct Work Viewed in 1965," The Kansas City Times, 7 August 1969. 17. "City to Pay in Bridge Case," The Kansas City Star, 31 August 1970. 18. "John Alexander Low Waddell," Civil Engineering 7 (January 1937): 77. 19. "Clausen Gold Medal Awarded,"Civil Engineering 1 (November 1930): 143. 20. John Lyle Harrington, ed., The Principal Professional Papers of Dr. J.A.L. Waddell (New York: Virgil H. Hewes, 1905): 3. 21. A comprehensive list of Waddell's publications from 1883 to 1920 can be found in J.A.L. Waddell, Economics of Bridgework (New York: John Wiley, 1921): 489-490. Other significant works by Waddell are mentioned in the text of this paper. 22. The Phoenix Iron Company was a joint firm of the Phoenix Bridge Company. 23. "J.A.L. Dies at 84," ENR News of the Week 120 (March 10, 1938): 354. 24. Diversity By Design: Celebrating 75 Years of Howard Needles Tammen & Bergendoff, 1914-1989 (Kansas City: HNTB, 1989): n.p. 25. Biographical information on Waddell was gleaned from several sources: "The Late Dr. J.A.L. Waddell," Engineering 145 (April 15, 1938): 413; Waddell and Skinner, ed., Memoirs and Addresses of Two Decades, 7-18 (see n. 19); Harrington, ed., The Principal Professional papers of Dr. J.A.L. Waddell, 1-11 (see n. 23); George F.W. Hauck and Louis W. Potts, "J.A.L. Waddell and the Diffusion of Civil Engineering Techniques," Civil Engineering History: Proceedings of the First National Symposium on Civil Engineering History (New York: ASCE, 1996): 53-65. 26. Armour-Swift-Burlington (ASB) Bridge or the Fratt Bridge. See George F.W. Hauck, The Builders of the Bridge: The Armour-Swift-Burlington Bridge in Kansas City and Its Influence on Engineering Practice (Kansas City: ASCE Kansas City Chapter, 1995). 27. The other Waddell "A" Truss is located in Shreveport, Louisiana. 28. This true-arch scheme was referred to in several of Waddell's publications. Unfortunately, these plans, along with the personal papers of both Waddell and Harrington, have not been located, if indeed they are extant.

| |||||||||

|

Bibliography (selected): "Construction of the Twelfth St. Trafficway Viaduct, Kansas City, Missouri," Engineering and Contracting 44 (October 27, 1915): 326-332. Fox, H. H. "Half-Mile Concrete Viaduct Provides Double-Deck Trafficway In Kansas City," Engineering Record 71 (January 6, 1915): 164-166. Fraserdesign. "Twelfth Street Trafficway [Viaduct]," Missouri Historic Bridge Inventory, September 24, 1994. Hauck, George F. W. and Louis W. Potts. "J.A.L. Waddell and the Diffusion of Civil Engineering Techniques," Civil Engineering History: Proceedings of the First National Symposium on Civil Engineering History (New York: ASCE, 1996): 53-65. Hool, G. A., et.al. Concrete Engineers’ Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1918. Howard, E. E. "The Twelfth Street Trafficway Viaduct, Kansas City, Missouri." ASCE Transactions 80 (1916): 484-532. Also referred to as Paper No. 1357 in the text above. "John Alexander Low Waddell," Civil Engineering 7 (January 1937): 77. Kansas City, Missouri, Ordinance No. 9820 Approved August 30, 1911 between the City of Kansas City and the receivers of the Metropolitan Street Railway Company. "The Twelfth Street Double-Deck Viaduct at Kansas City," Engineering News 73 (January 7, 1915): 10-15. Van Brunt, Henry. Letter to J.A.L. Waddell. Reproduced in J.A.L. Waddell, De Pontibus: A Pocket-Book For Bridge Engineers (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1898): 41-42. Waddell and Harrington. "Plans for Twelfth St. Trafficway Kansas City, MO." Varying dates from March 25, 1912 to April 15, 1916. Copy, Public Works Department, City of Kansas City, Missouri. See Historic Bridge Inventory report HERE

| |||||||||